#this chapter has Berthier in it too

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

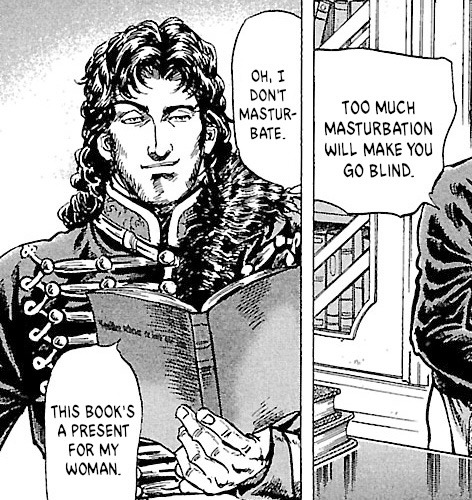

RP Murat reacts to Hasegawa Murat:

....

Is that supposed to be me?

Oh my god, look at me!

My compliments to my artist! He's made me so handsome and perfect here! "A captive of your love"? Yes, that's me, really, what's so terrible about saying that?

I can look at myself all day! Tetsuya Hasegawa has captured my essence, the essence that is Murat! 😘

I respectfully disagree. The key to a healthy and balanced life is taking some time out for yourself, if you get my meaning. Like with anything else, it's better with friends!

I breathlessly await your next installment, Monsieur Hasegawa. You've given me quite the introduction into this tale of your illustrated epic!

#tetsuya hasegawa#napoleon age of the lion#manga#RP Murat reacts#this chapter has Berthier in it too#oh my god Berthier#napoleon age of the lion vol 6 ch 037#napoleonic RP scene

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

I will have to read this chapter!

About Hoche: As far as I know, and much more likely than poisoning, he died of tuberculosis. Before dying, he recommended Gouvion Saint-Cyr as his replacement, but Lefebvre was designated instead.

About Marmont: He wrote a book called "L'Esprit des institutions militaires". It can be found on Gallica. I read it a little while back, and it appears to me to confirm what Soult stated about Marmont's theoretical knowledge. I think the book had some success at the time. It has chapters about just about anything to do with armies and their support systems.

About Marceau: He was only 26 when he was killed, too young to mature into a major military figure.

About Berthier: Although I strongly suspect Berthier of being a snob, Naps made it too easy for marshals and generals to hate him by making him his sometimes hatchet man and fall guy, all the better to deflect blame away from himself.

Kléber: As far as I know he was extremely capable; I am not surprised Soult admired him.

Soult on several French officers

This is taken from the book »Life of General Sir William Napier«, Volume 1. Soult, while in England for the coronation of Queen Victoria, talk to British historian Napier, who wants to know his opinion on several French officers. As usual, Soult is not very forthcoming, his statements are rather brief. There are longer ones on Hoche, on Napoleon and on Joseph Bonaparte, however, that I might post separately if there’s interest. Or you can just look them up yourself under the above link (page 505, bottom, ff, »Generals of the Revolution«). For once, it’s all in English. So, here are Soult’s verdicts on:

MARCEAU. “Marceau was clever and good, and of great promise, but he had little experience before he fell.”

This general I had to look up: He died from his wounds in Austrian captivity in 1796.

MOREAU. “No great things.”

AUGEREAU. Ditto.

JUNOT. Ditto.

GOUVION ST. CYR. “A clever man and a good officer, but deficient in enterprise and vigour.”

MACDONALD. “Too regular, too methodical; an excellent man, but not a great general.”

NEY. “No extent of capacity: but he was unfortunate; he is dead.”

VICTOR. “An old woman, quite incapable.”

There are some funny scenes with this marshal that Brun de Villeret describes in his Cahiers. Apparently, Brun needed to go calm down Victor on several occasions.

JOURDAN. “Not capable of leading large armies.”

MASSENA. “Excellent in great danger; negligent and of no goodness out of danger. Knew war well.”

That’s a little less praise for Masséna than in his memoirs. But Soult is all around bragging a lot in this conversation, though it’s hard to tell how much of it may have been jokingly. (Then again – Soult and joking? Probably not.)

MARMONT. “Understands the theory of war perfectly. History will tell what he did with his knowledge.” (This was accompanied with a sardonic smile.)

And of course refers to Marmont’s alleged betrayal of Napoleon in 1814.

REGNIER. “An excellent officer.” (I denied this, and gave Soult the history of his operations at Sabugal.) Soult replied that he was considered to be a great officer in France; but if what I said could not be controverted as to fact, he was not a great officer, his reputation was unmerited. (The facts were correctly stated, but Regnier was certainly disaffected to Napoleon at the time; his unskilful conduct might have been intentional.)

DESAIX. “Clever, indefatigable, always improving his mind, full of information about his profession, a great soldier, a noble character in all points of view; perhaps not amongst the greatest of generals by nature, but likely to become so by study and practice, when he was killed.”

KLEBER. “Knew him perfectly; colossal in body, colossal in mind. He was the god of war; Mars in human shape. He knew more than Hoche, more than Desaix; he was a greater general, but he was idle, indolent, he would not work.”

BERTHIER and CLARKE.

“Old women - Catins. The Emperor knew them and their talents; they were fit for tools, machines, good for writing down his orders and making arrangements according to rule; he employed them for nothing else. Bah! they were very poor. I could do their work as well or better than they could, but the Emperor was too wise to employ a man of my character at a desk; he knew I could control and tame wild men, and he employed me to do so.”

You could do Berthier’s and Clarke’s job easily, huh? Well, I could name one battle of Waterloo that says otherwise, Monsieur! (So does Napier, btw.)

I think between Berthier and Soult all bridges were burnt. And it really may have been not only from Soult’s side. I can quite imagine how somebody like Berthier, “l’homme de Versailles”, coming from a noble background and placing great value on politeness and good manners, would react to Soult.

#jean de dieu soult#louis-alexandre Berthier#auguste viesse de marmont#lazare hoche#napoleon#napoleon's marshals#napoleonic era#napoleonic history#napoleonic wars#jean-baptiste kleber

56 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello! Do you know why Berthier disliked Lasalle (if it's not about his brother's wife)? And where could I find more about this? Thank you 😘

The most commonly mentioned answer was Lasalle going after Berthier's brother's wife.

Which is honestly seems rather The Pot Calling the Kettle Black when Berthier also had a mistress?

Though I have no idea which book has the most Lasalle info.

Elting seems to have a somewhat negative assessment of Lasalle in Swords Around A Throne. Though he calls Lasalle without enemy but mentions Marbot disliked him but on a quick skim I didn't see what Marbot said about Lasalle in his memoirs. >_> I never finished reading Marbot's memoirs because I find him kind of annoying.

In Napoleon's Cavalry and its Leaders by David Johnson, there is a whole chapter for Lasalle but the Berthier's brother's wife incident is a very short paragraph.

Anyhow, now I am hunting through the stacks for who gives the most salacious version.

....god I wish more of my books had indexes. =_= I have too many books and my brain is soup.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jean-Baptiste Berthier

In honor of Berthier's birthday, I thought it would be interesting to know a little more about where he came from. Luckily I have a biography by Franck Favier, who has a whole chapter dedicated to the origins and social rise of his family. His father comes across as quite a successful and hard-working man. We can see how such a man would influence our Berthier's work ethics and character.

Please be indulgent, I translated this a little too fast to be really good, but I did my best to be in time.

What a destiny for this family of the Ancien Régime: in three generations, it climbed the ranks of society, passing from the status of ploughman to the splendours of Versailles, then to that of Prince of the Empire! The ascent surprised, because the Berthier family escaped the inevitability of a predetermined fate.

The Berthiers come from the village of Chessy-les-Prés, on the borders of Champagne and Burgundy. The great-grandfather, Rodolphe (1648-1710), was a ploughman, then a laborer. He married a ploughman's daughter, Marie Branche, in 1671. From their marriage were born at least two children who reached adulthood, François (1676), and Michel (1679). The first seems to have known a relative social stagnation by remaining a ploughman, while the second progresses: between the two births, their father Rodolphe passed to domestic service, in the service of Michel de Changy, Lord of Vézannes, who will be the godfather of little Michel.

This parrainage appears providential, because it allows Michel to escape the peasant world to embrace the career of wheelwright, probably with the wheelwright of the seigneury. He then emigrated to the town of Tonnerre, a classic sign of local rural exodus. In 1712, he married Jeanne Dumez, daughter of the servant of the bailiff of Noyers. The Lord of Vézannes still appears as a co-signatory of the act. From their marriage six children are born: four daughters [...] and two sons of whom only Jean-Baptiste, born in 1721, reaches adulthood [...]

Jean-Baptiste enters the service of the seigneurial family. Destiny steps in: Jean-Baptiste inherited from his wheelwright father qualities in mathematics and geometry which surprised his master. The latter then plays his connections, which allows Jean-Baptiste to enter the Ministry of War in 1739 as an instructor, then in 1741 as inspector general at the Ecole de Mars, military academy of Paris [...] There he was responsible for making young nobles maneuver. His studies subsequently pushed him from geometry to topography. As inspector, he proposed to modify the training programs and obtained a little more practice: he built on Ile aux Cygnes, in Paris, a miniature fort called Fort-Dauphin for the exercise of a siege. In front of the marshals of France and the people of Paris, the cadets and officers mimed the assault and the defense of the work.

However, it was during the War of the Austrian Succession that Jean-Baptiste's career took a new turn. In 1744 he obtained a lieutenancy and a job in the body of geographic engineers.

This body of engineers, founded in 1691 by Vauban, was made up of soldiers specializing in topographical surveys. They quickly distinguished themselves from ordinary engineers, more occupied with fortification work, and brought together experts recognized for their skill and dexterity in drawing up maps that were very useful for military strategies. The function required physical (endurance), but also intellectual (geometry, trigonometry and drawing) and military (fortifications) qualities. It repulsed highborn people, but was a means of social advancement for individuals of more modest condition.

In the aftermath of the Battle of Fontenoy (1745), Jean-Baptiste Berthier joined the army, assigned to the staff of Marshal de Saxe, commanding the army of Flanders, as an engineer geographer serving for reconnaissance of the camps , marches and locations of the king's armies. He took part in the Dutch campaign, was noticed at the battle of Lawfeld on July 1 and 2, 1747, where he was also wounded. The war allowed him to show his skills and courage on the ground. On this occasion, he established an album of twenty-five maps relating the main facts of the campaign, an album which he offered to the king.

His reputation being made, he can consider another means of ascension: marriage. On September 23, 1749, he married Marie Françoise Lhuillier de La Serre, born in 1731, whose father, César Alexandre, was captain of the castle of the Marquis de Breteuil, in charge of the surveillance and hunting of the estate [..] All were from recent nobility [..]

Jean-Baptiste thus entered the networks of geographers, important networks which tended to perpetuate themselves, by endogamy, in castes, without progressing, unlike the Berthiers. Fortune was to further benefit the family, already well served: on September 13, 1751, a fireworks rocket celebrated for the birth of the Duke of Burgundy set the Great Stable of the Palace of Versailles ablaze. Faced with the improvisation of the emergency services, Jean-Baptiste Berthier takes the responsibility of organizing the fight against the disaster, even putting his body on the line. Louis XV, who witnessed his exploits in person, would be grateful to him. He will thus enter into the favor of the sovereign. He will be in charge of multiple tasks, participating for example in the founding of the Military School of Paris from 1751 or also, through his plans and drawings, in the improvement of French military ports.

1753 saw the birth of his first son, Louis-Alexandre, the eldest of an upcoming series of twelve children, six of whom survived the horrors of infant mortality. In 1757, Jean-Baptiste acceded to the post of chief geographer engineer and to the direction of maps and plans of the Ministry of War. As such, he is in direct contact with the King and the Minister of War, to whom he can present each morning, with supporting maps, the operations of the French army during the Seven Years' War. As for his wife, she is assigned the much sought-after office of Monsieur's chambermaid. This charge made it possible to penetrate even further into the King's House. Monsieur will also honor the Berthiers by holding on the baptismal font one of their sons named after himself, Louis-Stanislas, born in 1767, while one of their daughters, Jeanne-Antoinette, born in 1757, had for godmother the Marquise de Pompadour.

[..]

The Duke of Choiseul demanded from Berthier the construction of the hotels of the Navy and Foreign Affairs. The work was quickly completed, in eighteen months. Speed, reasonable cost, architectural elegance, richness of ornamentation, ingenuity of interior design are admired by contemporaries [..] Moreover, always pragmatic, Berthier innovated in memory of the fire of 1751: he decided to replace everywhere the parquet floors with tiles, and developed a new system of incombustible brick vaults.

In July 1763, the king, as a reward, appointed him chief geographer of the king's camps and armies, governor of the War, Navy and Foreign Affairs hotels, and raised him to the nobility by letters patent established in Compiègne [..]

To these honors was added a salary of 12,000 pounds per year, half of which went to his widow and reversible to his children. It was the peak for Jean-Baptiste Berthier, who decided to have his portrait and that of his wife painted, signs of his notability. In 1765, he received the order of Saint-Michel, and two of his children have, as we have seen, illustrious godfather and godmother.

His new status giving him the privilege of being able to practice hunting, he associates the useful with the pleasant. At the request of Choiseul, then to that of the king, he established numerous hunting maps for most of the royal forests: Amboise, Rambouillet, Versailles, Marly, Saint-Germain, Sénart, Boulogne and Vincennes. This considerable work, unfinished during the Revolution, will be completed by his son, the future marshal.

[..] Having reached the peak of his career, Jean-Baptiste Berthier can look at his career with satisfaction. Despite his words: "I am no richer than when I was born in Tonnerre from the poorest citizens of this city", his rise is remarkable.

Beyond the titles and honors accumulated by the engineer Berthier, we will notice the extent of family and matrimonial alliances. The Berthier couple had twelve children, five of whom, along with the marshal, reached adulthood. Among those who survived, the two daughters, Jeanne-Antoinette (1757-?) And Thérèse (1760-1827) made excellent marriages [...] Of the four sons, three will be, under the Revolution and subsequently, illustrious soldiers: Louis-Alexandre marshal, Louis-César (1765-1819) and Victor-Léopold (1770-1807), major generals. The fourth son, Charles, born in 1759, nicknamed Berthier de Berluy to differentiate him from his elder Louis-Alexandre, died during the American expedition.

[..]

General Thiébault, then in garrison at Versailles, reports in his Memoirs of his meeting with old Jean-Baptiste in 1803.

"One morning, as I was having breakfast, a little old man who was still green came into my house, and who, in a deliberate tone, said to me:" Would you like, Monsieur le Général, to receive a visit from the father of the Minister of War, of General Berthier? " I hastened to answer that I would have hastened to offer this to him, if I had known that he was in Versailles, and I could have added if I had known that he was still in this world. He told me that he resided in Paris, but that, having come to Versailles on business, he had not wanted to leave it without seeing me. "From your place," he said, "I will visit, as is my habit, the Hotel de la Guerre which was built by me, where I lived so many years and where all my children were born. "I insisted that he do me the honor of having lunch with me, but he only accepted a cup of coffee, and the idea occurred to me to suggest that I accompany him to the Hotel de la Guerre, which he was delighted with. We left together, and if it had been about selling it to me, he could not have shown me this hotel in more detail and told me more exactly the history of all this construction from the cellars to the attics. When, after one hour, we reached the attics, he said: "This is the accommodation that I was occupying ", and having stopped in a rather small and more than modest room with alcove:" Here is ", he added with pride," where Alexandre was born. "And on this subject he recounted many memories to me. We would have been by the cradle of the Macedonian king that Macedonia could not have been complete. Convinced that he had kept this place for the last bouquet of what he wanted to show me and teach me, I thought I was at the end of my chore. I had already congratulated him on his legs which seemed to find in this building the vigor they had during the construction, when he warned me that what was most curious to see, was the roof. Immediately he passed through a window, and drawing me as if to a trailer, but running, climbing like a cat, he walks me from ridge to ridge, from gutter to gutter, at the risk of breaking my neck twenty times. "

Six months later he passed away. He had fulfilled his role of dynastic founder to the best of his ability. He endowed his descendants, either by marriages for his daughters, or by a perfect education for his sons. The fact that he gave Alexandre as a second name to his eldest son and César to his third son could presage Jean-Baptiste's military ambitions. He was not disappointed.

Franck Favier- Berthier, l'ombre de Napoléon

I hoped you enjoyed this!

#napoleonic#louis alexandre berthier#franck favier#berthier l'ombre de napoléon#jean-baptiste berthier#papa berthier#another tireless and skillfull berthier#the anecdote reported by thiébault made me smile#papa berthier would have whipped out the baby pictures if he could#also: proof that the ancien régime society wasn't that frozen that you couldn't make yourself a place#happy birthday berthier!

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Helfert, Joachim Murat, Chapter 1, part 2

Another brief snippet from a 19th century Austrian book on the final years of Joachim Murat.

Besides this great affair, or rather in the wake of it, there occurred all sorts of incidents of such a vexatious nature that one could indeed believe that the Paris court circles were specifically intent on making King Joachim uncomfortable with governing and pushing him to take a step similar to that taken by the Emperor's brother, Louis of Holland, over a year earlier. General Aymé, French by birth but in Neapolitan service, was arrested in Paris by the Duke of Rovigo's henchmen; La Vaugyon, the King's first aide-de-camp, was expelled from Paris and Naples at the same time; in Rome, General Miollis seized the Farnese property belonging to the Crown of Naples. In his own country, the king was as if under guardianship; the Napoleonic generals in Naples, Grenier and Pérignon, sometimes acted in a hostile manner against him, then again, which was still more hurtful to him, as if they were his well-meaning advocates and protectors. A journey undertaken by the queen to Paris at the beginning of October 1811 and her prolonged stay there seemed to bring the looming quarrel to a conciliatory conclusion: the seizure of the Farnese estates was lifted, Aymé was released from detention in Vincennes, Napoleon once again adopted a more friendly tone towards his brother-in-law. However, there were soon occasions for new misunderstandings and frictions, and what was even more alarming - just as with Louis and Hortense of Holland - discord was sown in Paris between the two spouses, who did not always agree in their views and were now also distanced from each other. Caroline seemed to feel at home in Paris and wanted her children to join her, but Joachim persistently refused.

Thus the Franco-Russian war approached, in the spring of 1812, where Napoleon could make good use of his brave brother-in-law, but also of his troops. It was not with an altogether light heart that Murat followed the call to the "Grande Armée", where the Emperor placed the command of the entire cavalry in his hands; for the fear did not leave him that his country might be stolen away from him behind his back, however valiantly he rendered service to the successes of Napoleon's arms. That this fear was not vain became evident from a remark of Alexandre Berthier, when Joachim, seeing that there was nothing to be done for the moment in the theatre of war in view of the sad outcome of the campaign, desired to return to his kingdom. "He considers him too good a Frenchman," insisted the Emperor's long-time confidant, "not to be convinced that Murat, if the good of France should require it, would not hesitate to offer his throne in sacrifice." When no answer came from Paris to Joachim's repeated requests for a leave of absence, he on his own authority placed the supreme command of the disrupted army that had been entrusted to him by the Emperor in the hands of Prince Eugène and returned to Naples, where the population, full of joy at seeing their worries about inclusion in the Grand Empire disappear, gave him an enthusiastic reception (January 1813). His relationship with Caroline, who had reigned during his absence, also seemed to have improved, although there were still many differences of opinion.

But his imperial brother-in-law had been injured beyond repair. If the situation had not been so critical, Napoleon - as he wrote to his stepson Eugène - would have court-martialled him to make an example. This did not happen, but the emperor ignored him completely; he did not write to him, but at the most to his wife. When he met the Neapolitan envoy in Paris, the Duke of Carignano, he inquired about Caroline's health, but never mentioned his brother-in-law. He sent back to him the Neapolitan regiments which had hitherto fought on the Iberian peninsula, and made absolutely no mention of if he were in further need of Murat's help in the war. The latter, for his part, seemed to know nothing of the French envoy at his court, only received Durand on solemn occasions like the representatives of all the other powers, and spoke in an unbound manner about the errors of warfare to which so fine an army had had to fall victim in the campaign of 1812.

~

As long as the power of Napoleon remained unbroken, no support could have been found for Murat on any side, if it had pleased the omnipotent one to let him descend again from the throne which he himself had bestowed upon him. Of all the European governments there had been at that time only two independent of the Emperor Napoleon: but Russia was then in firm league with France, England, on the other hand, was no less Murat's than Napoleon's enemy. Now things were different, and Austria was where the King first turned his eyes. His cabinet had been on particularly friendly terms with Austria since the official recognition from that side in the summer of 1811; Austria and its statesmen enjoyed many sympathies at Joachim's court, and it was Austria that at the present moment began to play an important role as a mediator in the great dispute, recognised by both sides. The personality of the Austrian representative at the Court of Naples was not without significance either; for Count Mier not only showed himself to be a prudent and confidence-inspiring diplomat, he also had an unmistakable affinity for the chivalrous king, whom he would soon assist almost as an adviser and confidant. Thus it came about that early in March 1813 Prince Cariati appeared at the Viennese Court as an extraordinary emissary of the King of Naples, where, although he had not been given any written authority for the time being, he was to establish confidential relations and in particular, in the event of the conclusion of a world peace, to strive for the general recognition of his monarch and the guarantee of his property. In addition, behind the back of the Neapolitan Minister of Foreign Affairs, Duca de Gallo, whom both King Joachim and the imperial envoy distrusted for good reasons, direct communication was maintained in the name and on behalf of King Joachim and Metternich in Vienna, whereby Murat declared himself prepared to do everything that would be demanded of him from Vienna and to arrange his actions in accordance with the signals he received from there. Throughout the month of April, Queen Caroline was still not in on the secret, but as time went on, she too was taken into confidence and now loyally adhered to her husband's cause.

I find the timeline quite interesting. If I’m not very much mistaken, this is also about the time when Montgelas in Bavaria starts to take up negotiations with the Austrians. And the Saxon king has fled to Prague and allegedly did the same thing there. So apparently at this time Metternich has already started a concerted effort to break up Napoleons overbearing empire which had become unsupportable for much of Europe. He will still do so in Dresden during his marathon meeting with Napoleon in June.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Berthier, Elisabeth, and Giuseppa.

Elisabeth is twenty-four, Giuseppa forty-three, and Berthier fifty-five. One can wonder about this cordial agreement, carried to an unusual degree, between two rival women. Because they will cohabit, Berthier not being able to bring himself to separate from Giuseppa, in the large hotel on the avenue des Capucines, but also in Grosbois where, if the Princess of Neuchâtel had her private apartments, the north pavilion was known to the inhabitants. of the castle under the name "apartment of Mrs. Visconti." Some will be shocked, such Augusta of Bavaria, the happy wife of Eugène de Beauharnais, viceroy of Italy, but also Elisabeth Berthier's first cousin. In a letter from Hortense de Beauharnais to her brother on August 23, 1809, she evokes the prejudices of Augusta, who has just met Giuseppa in Milan: "I received a letter from my sister-in-law who told me about Mme Visconti . She will no doubt have told you about it too: she cannot believe that her cousin is well with her and that she is even her intimate friend. This made her receive her coldly. The other, who is used to to be spoiled, will have been greatly astonished. I do not know what to answer my sister on that. She has the good fortune of being a princess without knowing a court and it is a great happiness. I was like her, but unfortunately, we learn every day, at our own expense, that we must welcome everyone. "

Hortense de Beauharnais is very severe here on the chapter of morals, she who will give birth two years later to the future Duke of Morny, born of her extramarital love with Charles de Flahaut, aide-de-camp to Marshal Berthier ... In addition, Augusta and Elisabeth were in different situations because if their marriage was organized without their consent, the first found love in Eugène de Beauharnais, the second came too late. Alexandre's heart was taken, and Elisabeth was not compelled to fall in love with a man without particular beauty and of her father's age. Consideration, tenderness, but no love, therefore no jealousy!

Franck Favier - Berthier, l’ombre de Napoléon

#napoleonic#franck favier#berthier l'ombre de napoléon#louis alexandre berthier#elisabeth wittelsbach berthier#giuseppa visconti#hortense de beauharnais#augusta wittelsbach de beauharnais#eugène de beauharnais#hortense's judgy side

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

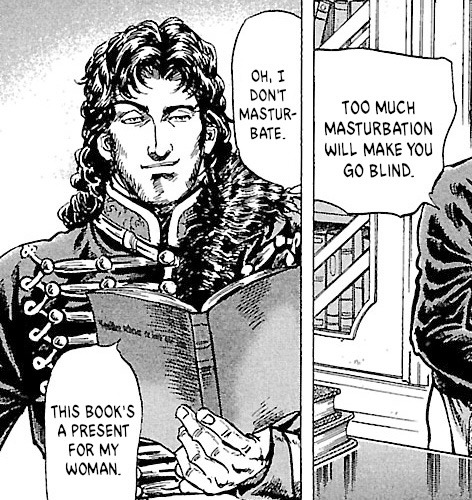

Reblogging this here from Murat's RP blog. Because oh my god.

RP Murat reacts to Hasegawa Murat:

....

Is that supposed to be me?

Oh my god, look at me!

My compliments to my artist! He's made me so handsome and perfect here! "A captive of your love"? Yes, that's me, really, what's so terrible about saying that?

I can look at myself all day! Tetsuya Hasegawa has captured my essence, the essence that is Murat! 😘

I respectfully disagree. The key to a healthy and balanced life is taking some time out for yourself, if you get my meaning. Like with anything else, it's better with friends!

I breathlessly await your next installment, Monsieur Hasegawa. You've given me quite the introduction into this tale of your illustrated epic!

#tetsuya hasegawa#napoleon age of the lion#manga#this chapter has berthier in it too#oh my god berthier#napoleon age of the lion vol 6 ch 037#napoleonic manga#napoleonic shitpost

21 notes

·

View notes